Florence Nightingale: Visionary for the Role of Clinical Nurse Specialist - On Medscape, a must read!

Posted about 5 years ago by Everett Sparks in Publications, Articles, Credits

Florence Nightingale: Visionary for the Role of Clinical Nurse Specialist

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Florence Nightingale is well known as the mother of nursing, aptly recognized as "Lady in Chief", immortalized as "the Lady with the Lamp", and revered as a visionary and a catalyst for healthcare reform. Nightingale's life and impact on patient care, nursing and nursing practice, and healthcare systems and organizations parallel the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) roles and three spheres of impact. In this article we highlight key events of Nightingale's work that illustrate her calling and devotion as a nurse and review her observations of organizations and nursing practice and her famous twenty-month experience (1854–1856) in the Crimean War at the British Army Hospitals at Scutari. Nightingale's critical thinking and problem analyses; implementation of interventions and positive outcomes; advancement of nursing practice based on evidence; detailed documentation and statistical analysis; and tenacious political advocacy to reform healthcare systems resembles the role of the CNS as an expert clinician, nurse educator, researcher, consultant, and leader in healthcare systems and policy creation. This article explores Nightingale's contribution to nursing practice and education as a visionary for the role of the clinical nurse specialist.

Introduction

Well-known as a visionary and a catalyst for change, Florence Nightingale broke barriers underpinned by her determination, her sense of moral duty and responsibility, and her political influence during a tumultuous era of war, diseases, and suffrage. This tenacity has resulted in outcomes that have transformed medicine to a higher level of diligence; advanced a framework for nursing practice and education; and influenced healthcare around the world in the fundamental areas of public health sanitation, infection control, nutrition, and health promotion. Additionally, Nightingale is celebrated as an administrator, patient advocate, hospital reformer, and pioneer in the use of statistics which she used to support her political activism. Her observations and passion for improving nursing practice and healthcare systems did not end until near her death in 1910.

In this article, through a review of the history of Florence Nightingale's seminal years in Turkey at Scutari during the Crimean War and her notes on nursing, the authors utilize her vision, ideology, and outcomes in nursing as a framework to characterize the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) role, a role that she exemplified during her career. The following section is an abbreviated review of Nightingale's work at Scutari includes topics noted that reflect today's CNS spheres of impact.

Nightingale's Work

Nightingale's initial observations on the administration of nursing and healthcare organizations began in 1851, first at the Kaiserswerth Deaconess Home in Germany and in 1853 on fact-gathering tours of hospitals in France, Austria, and Italy (Steward & Austin, 1962). In Scutari, concurrent with changes in hygiene practice and nursing care of the wounded, Nightingale initiated seemingly disparate wide-ranging projects to improve patient centered care, competence of the staff, and the healthcare environment. She surveyed the organization's human resources, determined the members for the interdisciplinary teams, and assigned them accordingly to set projects in motion to support the wellbeing of the patients.

For Nightingale to accomplish project goals, she identified root causes of problems, gaps, and then engaged accountable stakeholders, onsite and in London. In Scutari, she encountered reluctant stakeholders (e.g., jealous medical officers, bureaucratic men) and none were eager to take orders from or be outperformed by a female. She swayed their opinions through expert care, outcomes, and professional demeanor, eventually overcoming their skepticism because she sustained her focus 'for the sake of the work' (Andrews, 1929, pp. 146–147). Nightingale intuitively and wisely influenced local stakeholders by building onsite multinational teams whose collaborations were essential. The myriad individuals on the teams included her nurses; military medical officers and wives of soldiers; diplomats and their wives; local men of business and laborers; and religious sisters and clergy.

Nightingale was fluent in French, Italian, German, and Turkish. Her language skills became the glue that enabled her to direct team members to understand project scopes and work together for the common good. In addition, her other resources, including unrestricted funds provided to her by the War Office and her personal money, offered the means to assist with her projects. In London, the influential stakeholders were officials at the War Office, Queen Victoria, and aristocratic friends; among those opposing her work were the Prime Minister and Secretary of State. Like Nightingale's practice, the CNS role is independent and broad, and influences informed decision-making across changing environments, needs of populations, needs of organizations, budgetary appropriations, and regulatory mandates. CNSs are flexible and creative, adjusting their roles as Nightingale did when she leveraged her project resources in the face of one crisis after another.

Immediate changes occurred within days of her November 4, 1854 arrival to Scutari and by January 1855, Nightingale issued more than 6500 bed shirts and equal amounts of eating utensils from her inventory (Andrews, 1929). Existing food preparation was inadequate and there was often no fuel for cooking fires. Poor quality food was boiled in 13 copper cauldrons located at the one end of the hospital ward at distances of three to four miles through the corridors from individual soldiers (Cook, 1913a). Food was served cold, nearly raw, or cooked for hours depending on the distance from the cauldrons. Orderlies set the food beside the soldiers, expecting soldiers to feed themselves despite incapacities and handicaps such as upper extremity amputations.

Nightingale established new routines, breaking with those which hampered efficiencies established by the military medical officers. She determined which military and medical rules were sensible, and honored and respected these. Within ten days, at her direction, the engineers created two extra dietary kitchens and established three supplementary boilers (Andrews, 1929) which were used to make broths and a nutritious arrowroot supplement. Rejecting government supplied food, she used her money to buy food from local suppliers in Turkey. Nightingale wanted meat de-boned and gristle removed before serving, a request that caused medical officers to complain about giving "too much indulgence" to soldiers; they overruled her for that moment (Andrews, 1929, p. 149). Using immediate funds and her newly devised requisition system, Nightingale shortened the 2,000-mile supply chain from England to buy many goods and staples from local vendors (Cook, 1913a).

Role of a Clinical Nurse Specialist

Nightingale implemented changes and improvements in nursing practice and patient care, achieved outcomes and overcame barriers. So it is with CNSs in their roles. The ultimate goal is to optimize patient care and individualize care delivery to attain health for men, women, children, and the family in the context of their communities, just as Nightingale role modeled improvements and holistic care for soldiers at Scutari (Chan & Cartwright, 2014; Fulton et al., 2019; Heitkemper & Bond, 2004; McDonald, 2018; Miracle, 2008). Clinical nurse specialists number more than 70,000 advanced practice registered nurses (APRN) (NACNS, 2019) with clinical expertise in defined areas of nursing knowledge. They practice in every state, and exercise independent practice in 28 states and independent prescriptive authority in 19 states (NACNS, 2019).

CNS skills expand care delivery through research utilization to translate evidence into practice and to influence organizational and system levels (Heitkemper & Bond, 2004). The CNS scope of practice extends from wellness to illness and from acute to primary care and health promotion. CNSs engage in improving nursing practice through expert role modeling by mentoring and teaching nurses and healthcare professionals across all clinical settings (NACNS, n.d.).

Nightingale's beliefs about nursing standards and practice, advocacy and training; and impact within systems of care delivery are reflected in the CNS principles and spheres of impact: direct patient care; nurses and nursing practice; and healthcare environment, systems, and organizations (NACNS, 2019). The influence of Nightingale's analyses of poor performance gaps and her implementation of interventions to address deficiencies that affected the delivery of care in hospitals are evident across the newly expanded CNS spheres of practice.

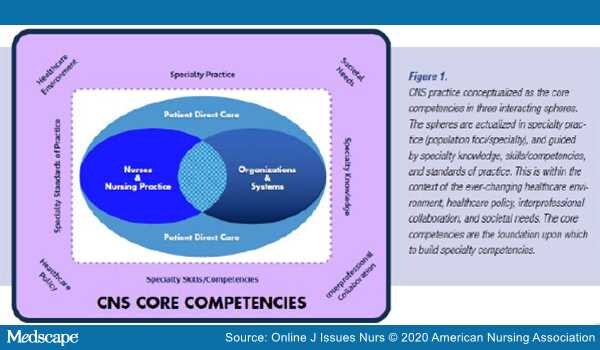

The expanded CNS spheres apply critical thinking skills to influence systems to enhance patient, family, and population care through forging and leading collaborative relationships; coordinating care across all levels; directing quality improvement projects; and devising innovative workflows. CNS clinical expertise competencies are assured by the specialty standards of practice and care within the nurse and nursing practice sphere. As Nightingale advocated for robust education for nurses, the CNS specialty directs specific knowledge, skill acquisition, and core and specialty competencies for in-depth clinical expertise and ever-changing nursing practice and healthcare systems (see Figure 1). These competencies describe the framework for the full CNS scope of practice. We will discuss these in greater detail in the following sections as we highlight the contributions of Florence Nightingale to the nursing profession.

Figure 1.

CNS Core Competencies

Sphere #1: Direct Patient Care

Nightingale independently developed her role, an unprecedented and pioneering feat. She also created roles for her staff that reflected patient need, directing interventions based on her observations, patient response, and utilizing best practices to advance patient outcomes. Nightingale and her nurses encountered neglected soldiers in agony who laid in filth, caked in blood, wrapped with putrefied bandages on festered wounds, pestered by vermin, naked with nothing for warmth, and so weakened from starvation they were unable to care for themselves (Andrews, 1929; Cook, 1913a). Her preliminary survey of Scutari's British Army Barracks Hospital revealed four miles of mattresses and bedding on floor planking placed in rows side-by-side 18 inches apart. Within these conditions were 1715 sick and injured soldiers, including 120 with cholera, and 650 severely wounded in the General Hospital; with an anticipated 500 incoming wounded soldiers from the battle of the Charge of the Light Brigade(Andrews, 1929; Cook, 1913a). Nightingale's assessment of the situation has similarities to the CNS patient direct care competency of conducting a comprehensive health assessment in diverse care settings including psychosocial, functional, physical, and environmental factors (NACNS, 2019).

Nightingale's first nursing directives delivered compassion to these patients through human touch and hygiene as nurses began to bathe and clean the soldiers, clothe and wrap them with blankets supplied by from her inventory, and feed them nutritious foods. Based on her assessments, Nightingale directed and delegated nursing care, demonstrating the CNS competency of implementing a customized evidence-based intervention (NACNS, 2019).

Nightingale and her nurses gained expertise as they worked endlessly at the bedside caring for wounded and dying soldiers, frequently participating in triage, surgery, wound care, and care of those with infectious diseases. Her ingenuity to ensure adequate nutrition promoted healing, thus reducing wound infections or development of cholera and dysentery. Despite multiple demands on her time, including her data collection and resource coordination, she never lost sight of the patients. It was reported that she was happiest during the time spent with patients (Gill & Gill, 2005). At night, she conducted patient rounds and used an oil lamp as her light. The soldiers waited for her. To see the Lady with the Lamp, or her shadow cast by its glow, gave them hope and a sense of belonging (Cohen, 1984).

Patient Care Outcomes. Nightingale's November 1854 arrival at the Barracks Hospital at Scutari immediately undergirded her appreciation of systems as she witnessed the chaotic and deplorable conditions with no coherent unified system of operation evident. Before leaving London's British War Office, her painstaking planning, foresight, and shrewdness finessed the Secretary at War to explicitly empower her with complete authority to command her 38 nurses and reform the situation, independent of the Medical Officers and Military Administrator (Andrews, 1929). Nightingale's skills here can be compared to CNS competencies of using advance communication skills in complex situations; use of evidence based knowledge to achieve outcomes; mentoring nurses and other professionals in evidence based practices; influencing systems changes; and leading and participating in systemic quality improvement and safety initiatives, (NACNS, 2019).

Through her expert clinical eyes she assessed the situation and began reforming care delivery for soldiers with comprehensive interventions, earning her the title: "Lady-in-Chief" (Andrews, 1929, p. 123). She directed her nurses to perform activities based on best practices and evidence for the day. Her evidence base was right in front of her. Men were dying at appalling numbers, not due to injury, but from diseases caused by terrible living conditions, poor care, and neglect of basic needs (Cook, 1913a). Like Nightingale, CNSs are renowned as change agents, influencers, leaders, and innovators (Chan & Cartwright, 2014). They are at the forefront in preventing hospital-acquired conditions (e.g., pressure injuries, bloodstream infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia), promoting improved patient outcomes, and reducing healthcare costs (Delp et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2014; Fulton et al., 2019; Heitkemper & Bond, 2004).

McDonald (2018) outlined eight key components of Nightingale's work and directives for high-quality nursing which parallel CNS interventions in patient care. These components include:

-

providing high quality compassionate patient care;

-

driving best practices based on advances in medicine and science;

-

implementing and monitoring of evidence based healthcare;

-

supporting high quality healthcare for all;

-

understanding that health status is linked to environmental conditions which is now termed 'social determinants of health';

-

collaborating across disciplines in coordination of care;

-

advocating for the health and welfare of nurses and their work environment; and

-

practicing as a political advocate for changing health systems

The CNS competencies of advocacy for principles to protect patient dignity and safety; using best practices and evaluating outcomes at the individual patient as well as system level; using leadership, negotiation, and collaboration to build partnerships; assessing and improving the nursing practice environment; and analysis of legislative, regulatory, and fiscal policies reflect the components of Nightingale's work.

Fulton et al. (2019) further delineated CNS workflows that improve patient outcomes through six common project implementation processes. These processes are:

-

identifying and situating a problem

-

engaging stakeholders and resources,

-

forecasting,

-

providing feedback

-

interfacing with the system, and

-

disseminating best practices

Nightingale, too, demonstrated each of the processes to achieve her project outcomes as she applied and evaluated care provision; engaged stakeholders; established and utilized standards of care; identified environmental factors that affected patient care and care outcomes; anticipated next steps; and disseminated her findings. To achieve her outcomes, she secured and channeled resources as she revised workflows and created new systems in a way similar to a CNS practice. This work demonstrates the CNS competencies of leading change in response to organizational needs and stewardship of human and fiscal resources (NACNS, 2019).

Cook (1913a), a contemporary of Nightingale who exalted her extraordinary abilities, revealed from her letters to him, "I work in the wards all day and write all night" (p. 234). Nightingale coordinated and oversaw care in the wards, keeping meticulous records about soldiers: their illnesses, recovery, or the causes of death. She recognized the value of data as a tool to improve care provided in hospitals and she standardized methods of collecting statistics (Cohen, 1984). Because of these data documentation and her persistence, she successfully anticipated, proposed, and justified to the British Government the administrative and practice reforms that she proposed would reduce the morbidity and mortality rates of soldiers. This practice is described in CNS practice as the dissemination of CNS practice and fiscal outcomes (NACNS, 2019).

Validating Outcomes With Data. Nightingale was familiar with the medical advances and current evidence of the time, such as contagion of disease and its proximity to unsanitary conditions. She noted these associations through her first independent assignment with actual nursing and leadership at Middlesex Hospital during a cholera epidemic (Steward & Austin, 1962). She was a proponent of the early sanitarian movement that created the 1848 British Public Health Act (Gill & Gill, 2005). She implemented into practice what would be the first tenets of germ theory in disease prevention by emphasizing the values of cleanliness and antisepsis, clean air, water, and nutrition. Her hygiene practices and isolation of infected patients to prevent spread of disease are forerunners of current infection prevention practices (Gill & Gill, 2005).

She was instrumental in validating the need for improving sanitation, nutrition, and ventilation of the wards. As a result of these onsite sanitary reforms, the hospital mortality dropped an unprecedented rate, from 42.7% to 2.2% (McDonald, 2014; Miracle, 2008; Neuhauser, 2003). These activities are well known to CNSs who use the scientific approach, scientific research, and scientific methods that provide valid data (NACNS, 2019) and evaluate the impact of nursing interventions on patient outcomes (NACNS, 2019).

Another contribution that Nightingale made to medicine was the remarkable application of a novel statistical tool, the color-coded coxcomb diagram for ready visualization, giving ease of interpretation by anyone (McDonald, 2014). She valued the experiences she learned in these army hospitals and later, when designing the curriculum for nurses, she ensured that basic practices of hygiene and germs as infectious agents were taught to the students (McDonald, 2010). Today's CNSs facilitate education and disseminate new knowledge for nurses and other healthcare professionals through interprofessional collaboration and teaching at the bedside, in university classrooms that include medical schools, and during professional training (NACNS, 2019).

Sphere #2: Nurses and Nursing Practice

Education and mentoring are interwoven in the CNS impact spheres and competencies of nursing practice. These concepts mirror Nightingale's framework for nurse training and care provision. While at Scutari, she mentored her nurses so their expertise would broaden, especially in wound care, and as she rotated her expert nurses to other area military hospitals. They, in turn, would then educate staff (Cook 1913a).

Nightingale also trained orderlies and championed better work conditions for them. After the war, she advocated for the Army Medical Department to train military orderlies in the personal care of soldiers. At the completion of their training, the orderlies were required to demonstrate competencies to receive their qualification certificates from nurse matrons. The certified orderlies would be permanently assigned as attendants and not rotated out to the battlefields (Andrews, 1929). Nightingale published her education findings and thoughts to inform each healthcare discipline and supporting stakeholders about the importance of education and the benefits of evidence-based care on patient outcomes (Conard & Pape, 2014).

Nurses and Education. By 1859, Nightingale had spent many hours contemplating what nursing is and what it is not, described in her famous writing "Notes on Nursing" (Baly, 1997; Cook 1913a; 1913b; Nightingale, 1859). She believed that nursing was a science and an art developed by practice and discipline. She was adamant that the nurse was not just an assistant to the physician (Baly, 1997) and that training embodied teaching the nurse to help the patient live well (McDonald, 2018).

Nightingale's goals for the nursing profession were to organize and standardize the education of nursing (i.e., training) and raise nursing to a respectable profession (Judd & Sitzman, 2014) through enlisting and training pupils of good character and morals; role models of compassion and empathy; and influencers of other caregivers. Her contemporary stated she sought "to raise nursing to the rank of High Art" (Cook, 1913a, p. 448). As she developed formal nursing education, she based it on her experiences in Crimea, with a focus on improving patient care (Conard & Pape, 2014). Nightingale believed that schools should be independent of hospital control, but near to hospitals where practical training was available (Steward & Austin, 1962). Through public contributions and the support of Queen Victoria, Nightingale actively raised enough money to fund the Nightingale School; a sum equivalent to $250,000 in 1860 (Sparacino, 1994).

Nurse historians place the beginning of the profession of nursing in 1860 when London's Nightingale Training School for Nurses at St. Thomas Hospital opened as the first organized training school (McDonald, 2018). Nightingale's legacy is that of the first modern nurse educator and this legacy is the one most individuals, lay or professional, identify for her (Conard & Pape, 2014). Her first graduates were her "Nightingale Nurses." These women were trained for assignments in hospitals to foster nurses and nursing practice; to develop nursing care systems; and to teach, train, and mentor others in their quest to become nurses (Steward & Austin, 1962).

On both sides of the Atlantic, trained nurses sought 'registration' to distinguish themselves from lay nurses. For seven years, Nightingale strongly opposed state registration of trained nurses; initially she felt nursing was a 'calling' for those with exemplary personal character and this could not be 'tested' (Andrews, 1929). In the 1880s and 1890s, draft regulations for registration were circulated by some nurse leaders in the British Nurses Association (Helmstadter, 2007). Nightingale analyzed the proposals (with the accompanying background politics) and felt state registration: would exclude working class nurses; was dependent solely on a written examination, with no account for compassion and skills; lacked adequate controls to prevent medical men from controlling the profession, "making nursing a legal profession inseparable from medicine" (Helmstadter, 2007, p. 160); and, finally, the intent of the leaders lacked professional ethics (Helmstadter, 2007). Her stance was registration should be centered on clinical competence and expertise evaluated by nurse experts currently working or training nurses (Helmstadter, 2007). Her education and advocacy directives are similar to those of the modern CNS and incorporated into the core competencies for nursing practice as CNSs facilitate professional development opportunities for nurses, students, and staff in the acquisition of knowledge (NACNS, 2019).

Advanced Nurse Practice and CNS. It is historic that Nightingale was influential in advancing the profession of nursing, but she also cultivated advanced practice nursing and the CNS role by promoting trained nurse leaders who challenged accepted practices and promoted evidence-based practice (Conard & Pape, 2014). Graduate education for the modern CNS role was created in 1954 by Peplau to provide leadership for direct specialty care for patients with complex diseases; to improve patient outcomes through the advancement of staff nurses' skills; and to aid retention of expert clinical nurses (Peplau, 2003). Nightingale's model for education laid the foundation in the 1960s for advanced practice nursing and expanded graduate level education (Judd & Sitzman, 2014). In 1966, the American Nurses Association introduced the resolution that all education for nurses take place in institutions of higher education and identified a baccalaureate degree as minimum preparation for a professional nurse (Judd & Sitzman, 2014). The CNS role has evolved for over 60 years. Initially part of the American Nurses Association, the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialist (NACNS) was established in 1995. The first statement on CNS practice and competencies was published in 1998 (Lyons, 1998) and recently revised in 2019 (NACNS, 2019).

Nursing Practice and Environment. CNS clinical competencies consider social determinants of health (SDOH) as an important aspect of CNS practice. Although SDOH is a more modern term, it is not new in respect to the work of Florence Nightingale. Nightingale's actions and writings demonstrated that she considered housing, social supports, access to healthcare, employment, and education crucial and interrelated to a person's health and wellbeing. Similarly, SDOH are important to CNS practice. Nightingale improved the healthcare environment for staff and soldiers by designing, renovating, and building to improve system efficiencies and workflows. Early on, she created spaces away from medical wards to promote the social wellbeing of soldiers by assigning the wives of diplomats to engage them in therapeutic activities, such as reading books to them or writing letters for them (Andrews, 1929). The CNS is a provider and leader in navigating individual, environmental, and community resources to address SDOH for care coordination and care transitions, and in reducing hospital length of stay, readmissions, and hospital-acquired conditions (NACNS, 2019).

Sphere #3: Organization and Systems

Outcomes Documented. Over her twenty months in Crimea, Nightingale logged in and out such data as the number of shirts she issued (50,000); the number of utensil kits, plates, pillows, blankets, uniform trousers, boots and socks, cots and bedding, tables and chairs; and types and amount of foods. Nightingale often worked twenty hour days. During the night hours she documented her observations, comparing any intervention or practice to ascertain the better outcome. For example she considered outcomes between individual physicians and their surgical techniques, or the care her nurses provided for the wounded that improved healing (Andrews, 1929; Cook, 1913a). She wrote lengthy letters to the Secretary at War and upper level government officials in which she revealed deficiencies she discovered, proposed remedies, and requested supplies and money. She grounded her persuasive narratives in statistical evidence. Many letters were read by Queen Victoria who applied further influence to speed supply deliveries; support Nightingale's stop-gap reforms that led to long-term changes; and assure that Nightingale's requests were considered and met. Similar to Nightingale's documentation and recommendations, today's CNS disseminate information about their practice, findings, and outcomes to internal stakeholders (NACNS, 2019).

"Notes" for Healthcare Policy. Nightingale's advocacy themes urged reforms that affected many aspects of society and its health beyond reform to improve soldiers' military service. From her Scutari correspondence to the War Office, based on the evidence she provided, an 1855 Report upon the State of the Hospitals of the British Army in the Crimea and Scutari was produced. In 1856, Nightingale was sickened by amoebic dysentery which caused her to be an invalid until her death in 1910. After her convalescence in England, she began 50 years of documenting her observations and proposals for policy changes, referring to these observation as "Notes."

Nightingale wrote 147 printed writings, the first in 1851 describing her experience at Kaiserswerth, and concluding in 1905 with a Message to the Crimean Veterans. She was a prolific writer and often was the silent author for Blue Books, official investigation reports from Royal Commissions that were presented to Parliament and the Queen. She was occasionally mentioned in these reports or had short sections attributed to her. However, in the private notes and the diaries of her male administrative partners, the truth is written that the work was done and reports written by Nightingale and were given credence because their male names and titles were on the documents (Cook, 1913b).

Her first "Notes" was Notes on Matters Affecting the Health and Efficiency of the British Army; from this publication, the government ordered a Royal Commission with a resultant Blue Book published in 1858: Report of the Commission which included a section noted as the Mortality of the British Army, at Home and Abroad, and during the Russian War [Crimea; Scutari], as compared to the Mortality of the Civil Population of England. Illustrated by Tables and Diagrams (for which she was credited).She pressed for creation of four sub-commissions that undertook reforms in sanitation for soldiers' living barracks and the hospitals; creation of an Army Statistical Department; formation of an Army Medical School; and reconstruction of the Army Medical Department, the Hospital Regulations, to establish competency standards for the Promotion of Medical Officers; and creation of training standards for orderlies (i.e., what we now call unlicensed assistive personnel) (Cook, 1913a).

Nightingale was adamant that female nurses could execute duties advantageous to military hospitals and in 1857 wrote a memorandum to the Secretary of State and in 1858, Subsidiary Notes as to the Introduction of Female Nursing into Military Hospitals in Peace and in War. She then published her Notes on Hospitals on the organization and administration of hospitals, and in 1859, the first edition of Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not (Nightingale, 1859). Nightingale integrated her observations and knowledge and determined new directions and roles for trained healthcare personnel. CNS practices include evaluation of systems level interventions and programs to achieve outcomes through promoting the profession of nursing's unique contributions to advancing health to organizations, community, public and policymakers (NACNS, 2019).

Outcomes Through Change Agency. Nightingale's leadership brought about change through her competencies, masterful will, and an uncanny strength; this became known as "The Nightingale Power," both mysterious and fabulous (Cook, 1913a, p. 214). CNS leaders cultivate power and influence cumulatively from their attributes, intentionality, supportive relationships, communication skills, coalition building, and rational persuasion (Adams & Natarajan, 2016; Fulton et al., 2019). The CNS intentionality and consistency in practice gains respect and often the CNS becomes a key professional in accomplishing the strategic goals of the organization. Magnet designations, which are peer reviewed affirmation of excellence, have been attributed to CNS leadership as their power and ability to create interprofessional collaboration supports nurses and nurse practices in the quest for direct patient care through organization (Fulton et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2009). Across settings, CNSs utilize their knowledge and skills to influence every aspect within their spheres of impact.

Conclusion

The role of the CNS was created to meet increasingly complex and evolving needs of patients and communities. This resembles the mission undertaken by Nightingale and her vision of nursing. The CNS spheres of impact affect each aspect in patient care; nursing and nursing practice; and healthcare systems and organizations, reflecting Nightingale's work and beliefs about patient care, nursing standards, advocacy, and training. CNSs demonstrate their influence and impact on systems of care delivery, which resonates with Nightingale's vision of healthcare. Lord Dean Stanley stated Nightingale used her "commanding genius" (Andrews, 1929, p. 143) as she confronted the challenges of her era just as modern CNSs address the complexity of healthcare when providing quality services to rural and urban underserved populations, the aging and disabled, and patients with multiple chronic conditions. Just as Nightingale's aspirations were to always strive toward improvement and perfection and to make nursing a 'High Art,' the CNS endeavors to meet the nursing challenges of our patients, organizations, society, and profession. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1857) described Nightingale and her compassion the most elegantly as,

"A lady with a lamp shall stand.

In the great history of the land,

a noble type of good,

heroic womanhood."

References

-

Adams, J. M., & Natarajan, S. (2016). Understanding influence within the context of nursing: Development of the Adams Influence Model using practice, research, and theory. Advances in Nursing Science, 39(3), E40–E56. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000134

-

Andrews, M. (1929). A lost commander: Florence Nightingale. Doubleday.

-

Baly, M. (1997). Florence Nightingale and the nursing legacy: Building the foundation of modern nursing and midwifery (2nd ed.). Bainbridge Books.

-

Chan, G. K., & Cartwright, C. C. (2014). Advanced practice roles: Operational definitions of advanced practice nursing: Clinical nurse specialist. In A. B. Hamric, C. M. Hanson, M. F. Tracy, E. O'Grady (Eds.), Advanced practice nursing: An Integrative approach (5th ed., pp. 359 – 391). Elsevier Saunders.

-

Cohen, B. (1984). Florence Nightingale. Scientific American, 250(3), 128–137. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0384-128

-

Conard, P., & Pape, T. (2014). Role and responsibilities of the nursing scholar. Pediatric Nursing, 40(2), 87–90.

-

Cook, E. T. (1913a). The life of Florence Nightingale. (Vol 1). Macmillan.

-

Cook, E. T. (1913b). The life of Florence Nightingale. (Vol 2). Macmillan.

-

Delp, S., Ward, C. W., Altice, N., Bath, J., Bond, D. C., Hall, K. D., Harvey, E. M., Jennings, C. D., Lucas, A., Whitehead, P., & Carter, K. (2016). Spheres of influence…clinical nurse specialists: Sparking economic impact, innovative practice. Nursing Management, 47(6), 30–37. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000483132.20566.cd

-

Duffy, M., Daniels, K., Mittelstadt, P., & Muller, A. (2014). Impact of the clinical nurse specialist role on the costs and quality of healthcare. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 28(5), 300–303. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000074

-

Fulton, J. S., Mayo, A., Walker, J., & Urden, L. D. (2019). Description of work processes used by clinical nurse specialists to improve patient outcomes. Nursing Outlook, 67(5), 511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.03.001

-

Gill, C. J., & Gill, G. C. (2005). Nightingale in Scutari: Her legacy reexamined. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 40(12),1799–1805. doi: 10.1086/430380

-

Heitkemper, M. M., & Bond, E. F. (2004). Clinical nurse specialists: State of the profession and challenges ahead. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 18(3), 135–140. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200405000-00014

-

Helmstadter, C. (2007). Florence Nightingale's opposition to state registration of nurses. Nursing History Review, 15(1), 155–165. doi:10.1891/1062-8061.15.155

-

Judd, D., & Sitzman, K. (2014). A history of American nursing: Trends and eras (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett.

-

Lyons, B. (1998). NACNS Statement on Clinical Nurse Specialist competencies and education is approved. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 12(1), 3–5.

-

Longfellow, H. W. (1857). Santa Filomena. Poems of Places.

-

McDonald, L. (2010). Florence Nightingale a hundred years on: Who she was and what she was not. Women's History Review, 19(5), 721–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2010.509934

-

McDonald, L. (2014). Florence Nightingale, statistics and the Crimean War. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 177(3), 569–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12026

-

McDonald, L. (2018). Florence Nightingale: Nursing and health care today. Springer.

-

Miracle, V. A. (2008). The life and impact of Florence Nightingale. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 27(1), 21–23. doi: 10.1097/01.DCC.0000304670.76251.2e

-

NACNS. (n.d.). Scope of practice. https://nacns.org/advocacy-policy/policies-affecting-cnss/scope-of-practice/

-

NACNS. (2019) Statement on clinical nurse specialist practice and education (3rd ed.).https://portal.nacns.org/NACNS/Store/NACNS_StatementOnCNSPractice.aspx

-

Neuhauser, D. (2003). Florence Nightingale gets no respect: As a statistician that is. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 12(4), 317. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.4.317

-

Nightingale, F. (1859). Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not. Harrison.

-

Peplau, H. (2003). Specialization in professional nursing. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 17(1), 3–9. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200301000-00002

-

Steward, I., & Austin, A. (1962). A history of nursing: From ancient to modern times, a world view(5th ed.). G.P. Putnam's Sons.

-

Sparacino, P. (1994). Florence Nightingale: A CNS role model. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 8(2), 64. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199403000-00002

-

Walker, J. A., Urden, L. D., & Moody, R. (2009). The role of the CNS in achieving and maintaining Magnet status. Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(1), 515–523. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181c1803a

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge Kimberly Carter, PhD, RN, NEA-BC for her thoughtful review and critique of this manuscript.

Online J Issues Nurs. 2020;25(2) © 2020 American Nurses Associatio

Comments

No comments yet.

Only active members can comment on this announcement.

Learn more about membership